It’s my own design, it’s my own remorse, help me to decide, help me make the most of freedom and of pleasure, nothing ever lasts forever

Lyrics from a song I have only vague conscious awareness of from my youth

Are young children really good or really bad at drawing people? They typically draw big melon heads that are too circular and out of proportion with the body, and those ginormous heads have ginormous eyes placed too high on the face. Then there’s a massive, stupid grin. Realistic to them? Conveying something important? Obviously, it looks “wrong” next to a photo or what we experience as adults, but how do we know if our experience as adults is “realistic”?

Have you photographed the full moon on the horizon? Here’s a typical photo.

Here’s “reality” in your mind:

Even as adults we continue to experience the so-called “moon illusion,” the purported explanation for why the moon on the horizon (and mountains and prominent buildings in the distance) look awesome but are supposedly “wrong.”

There seem to be two competing “worlds.” One paints the big picture with what we feel is important and one works with and manipulates details. Here’s an account of what’s going on and how we got there.

Welcome to your life, there’s no turning back. We come into the world and start experiencing it. Early on, it’s nearly all right brain. We know from studies of people with brain damage and experiments that manipulate which hemisphere gets information that the right brain reads eyes and faces and emotions. People with right-brain damage struggle to understand anything implicit in what someone is communicating. They tend to focus on the speaker’s mouth instead of the eyes and can’t read emotion, deceit, or understand jokes or metaphors. They take everything literally and seem stupid.

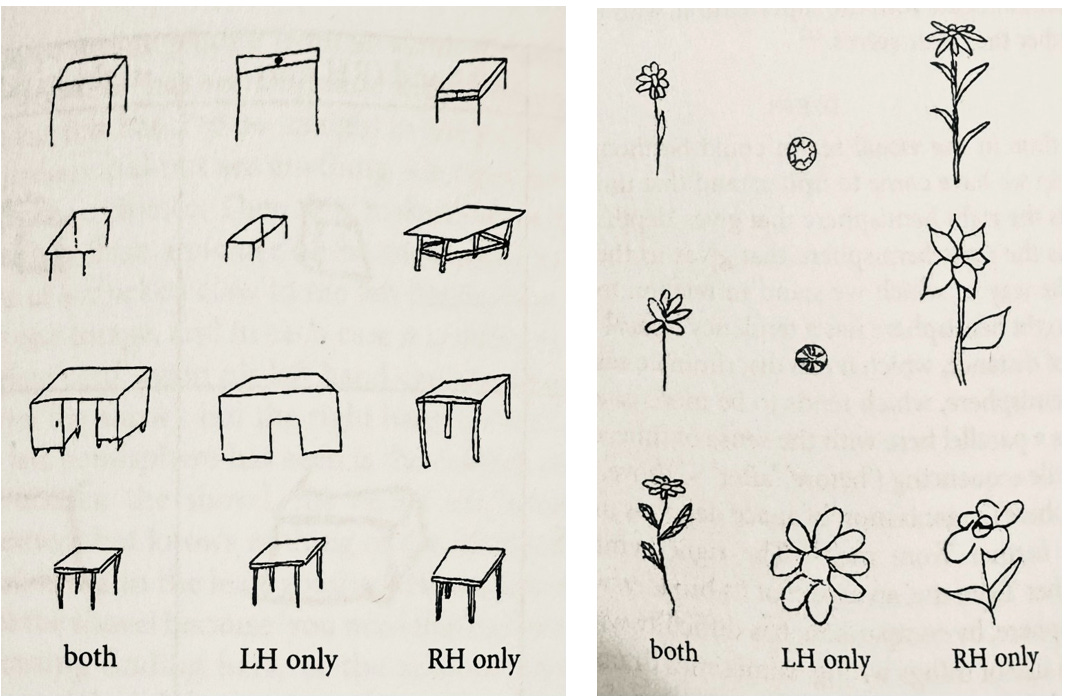

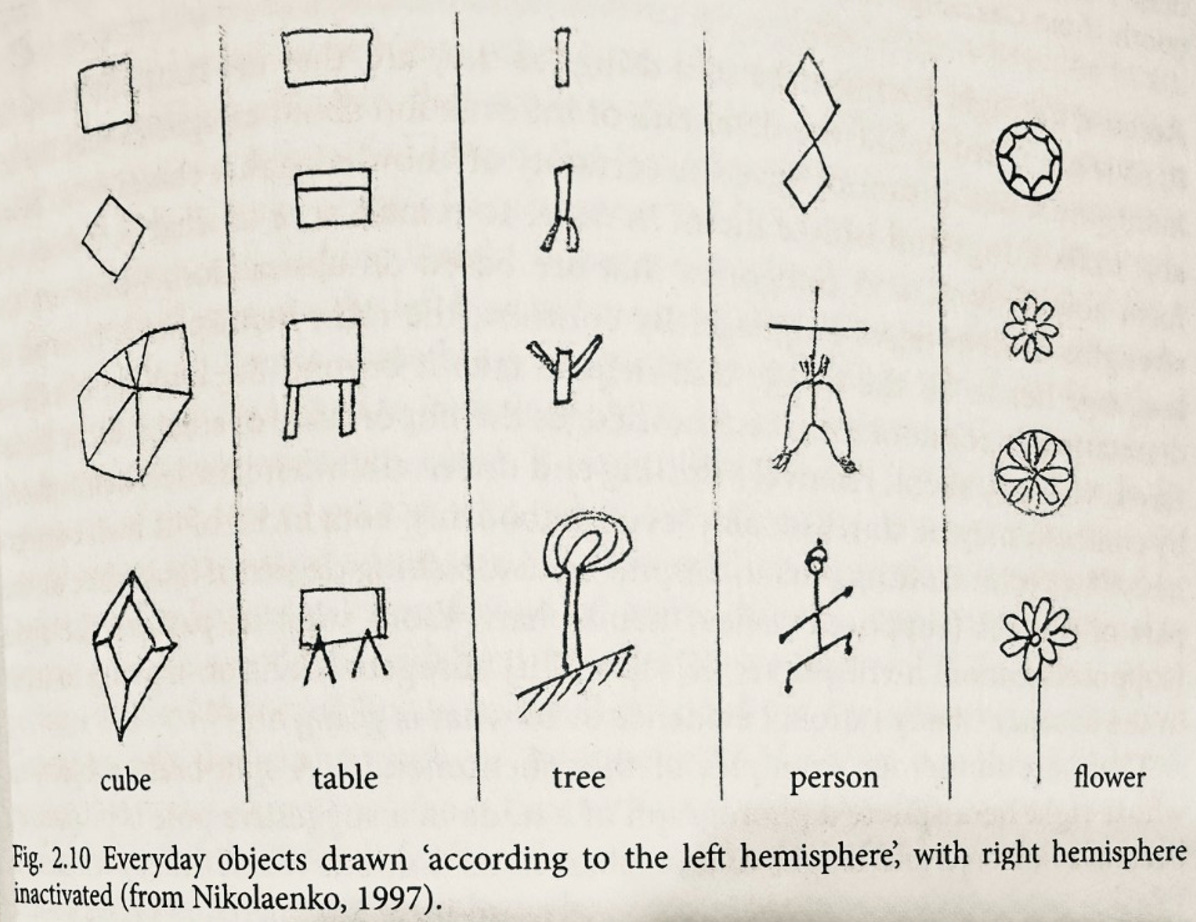

They also can’t draw well. The depictions below are in The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, a quite fascinating book by Iain McGilchrist. The researchers designed experiments for participants to draw normally (both hemispheres), use just the left hemisphere (LH), or just the right hemisphere (RH). With the exception of one person who nailed the table all three ways (perhaps because of some training, see note 2 infra), the differences are stunning:

The left-brain drawings are mostly just flat details or utterly confounded. And the right-brain drawings are even better than the normal ones. What gives?

It seems the left brain “knows” things by details and the rules and concepts it has for the known object. Flowers have petals, tables have legs, people have bodies and limbs, etc. The left brain also likes straight lines and angles and struggles with curvature and depth. The right brain, by contrast, “sees” and “knows” the whole with depth and roundness.

Both sides are trying to understand the world in different ways. While drawing the world may separate us from the animals, dealing with the world conceptually does not. Animals have split brains, too. And the left side creates concepts to make the most of freedom and of pleasure by getting what it needs now because nothing ever lasts forever. Thus, a chick—focusing with its right eye (left brain)—uses rules for the world about how something of a certain size and shape might be food and pecks at it.

We do the same (only our eyes are each split, with the left hemisphere of each being right-brain and vice-versa). And we go far beyond food with our rules and concepts. Indeed, once our left-brain really comes on-line with speech, we turn our back on Mother Nature to some extent. Instead of being “present,” we work with our symbols for the world (like words, speech is left brain) and our internal re-presentations of it. Basically, the left brain starts giving us virtual reality.

And we need that reality-management so we can function and “pay attention” to whatever we must attend to, including anything that seems new. Eventually that new thing will receive some concept or rule, and into the mental wallpaper it will go. It’s what we do. We slap rules on our world to understand it and manipulate it and have it not kill us or make us sad. Maybe, in “reality,” there are no rules. But we rule up the world for our survival.

So how should we think about law? Law seems like a pretty obvious and intentional manifestation of creating rules for the world. It’s all about rules. Indeed, some have said that the “rule of law” should aspire to be a “law of rules,” and that in America “the law is king,” as opposed to some king being the law.[1] Thus, it ought to be at least modestly important when engaged in legal writing to identify some rules.

Several years ago, I asked a very intelligent and accomplished friend of mine, one of my favorite people to discuss legal writing and judicial decisions with, what is the #1 thing legal writers need to focus on to improve? The answer: “bring forth the syllogisms.” (So well put.)

What’s a syllogism?

Step 1: there is a rule, e.g., if A then B.

Step 2: application (usually some facts), what we’ve got here is an A.

Step 3: conclusion, since we’ve got an A then by rule we have B.

Rule. Application. Conclusion. The RAC of I-RAC. The logos of Ari-STOT-los (nickname when he got buff). (For my previous discussion of Aristotle and logos, see here.)

The gist of my friend’s syllogistic advice was that legal writers need to work harder at finding and constructing rules. And once they’ve found or created some rules, they need to feature that logical construction in the brief: the RAC, the logos, the Aristotliness. Here’s the rule, we fit, we win.

All of which begs the question: if writers aren’t doing that, what the hell are they doing?

As I’ve observed previously, one hallmark of poor legal writing is over-obsession with finding snippets of things people in black robes once said, like those little chicks pecking at tiny stones for food, and then it’s gathered up and delivered with foul balls (tip #5), irrelevant facticity (tip #6), and explanatory parentheticals (tip #9). But a little pile of grain is not a croissant, just like five noses and an ear is not a face. The writer needs to bring all that stuff together with some curvature and depth to get a picture, otherwise it’s indecision married with a lack of vision. At best, it’s a crappy left-brain table.

Constructing a rule for your syllogism is tough when it’s not obvious, and I don’t know if truly inspired rule-construction is very teachable. But there are ways to “bring forth the syllogisms” like learning the basic proportions of the human face or the rules of perspective to draw better.[2]

The big thing: start with the text. Perhaps it is a statute, rule of civil procedure, regulation, or a provision in a contract. I knew an in-house attorney who had beneath his signature block a motto (or primal scream, though he didn’t seem like a screamer): “What does the contract say?” There are lots of times when the rule you’re looking for is literally a rule of law, or a rule found in a legal document. Start there.

After that, perhaps courts have coalesced on what key words mean. Or maybe they’ve fashioned some test. After the text, we need that test. But then we may need to formulate a rule out of the various applications of the test. Prime rule-construction site, but pecking through applications is not the end goal. We need rule-construction from those applications so we can bring forth a syllogism. That’s the goal.

There are many more complicated situations. Maybe courts have never done something. That can be rule-like. Instead of “if A then B,” it’s “with A we’ve never seen B.” Don’t show me a bunch of rocks that look like food, give me the rule that says the food the other side says exists does not exist.

Why I like the admonition “bring forth the syllogisms” is that it gives writers a clear direction and structure. It’s actionable. And why provide rules and syllogistic reasoning? Because we are hard-wired to use rules to explain the world; because the eventual opinion will attempt to display logical reasoning 99% of the time; because courts need rules for practical administration of the law; because adhering to a rule achieves fairness and equity “without respect to persons” as is sworn in the judicial oath; and because “rule of law” beats “rule of elderly lawyers in black robes who decide case by case who they like more.”

I can hear the critics and skeptics and even the neuroscientists. “They say they’re following a rule, but they never, never, never, never need it. They decide based on feeling and intuition and the ‘reasoning’ is post-hoc rationalization, which is what the left-brain always does.”[3]

Perhaps. It certainly can be like that. All a game, symbol manipulation, just using the “tools” to achieve an objective. Less sinisterly, maybe we just don’t have a good internal sense of how we reason (which the neuroscience strongly suggests is the case). But there are practical and ethical/equity reasons to favor “rules,” as noted above. And as McGilchrist shows repeatedly, the right brain is very much the source of inspiration, understanding, and human connection. The most brilliant advances in conceptions and rules for the world are acts of creativity inconceivable without right-brain primacy.

Formulating rules with depth, discerning subtle and implicit connections, seeing the curves—that is the right brain. Indeed, that is not even something that happens through focusing narrowly on a problem. It might come to you while taking a shower. For the creative ideas, it’s like even while we sleep we will find you. The left-brain is no more up to that task with its narrow-eyed pebble-pecking than it is of drawing a decent face, much less an angry, happy, or loving one.

So rules for the world (or the law) differ in source, inspiration, scope, complexity, and beauty. But everybody wants to make rules for the world. It’s my own design. It’s my own remorse. And since every syllogism must have a rule, and the rule of law is mostly rules, it’s a good piece of practical advice when making legal arguments to bring forth the syllogisms.

And if the rule you construct for that syllogism looms larger than life on the horizon and transfixes some human being and helps them to decide, that’s no illusion. That’s human persuasion.

[1] Antonin G. Scalia, The Rule of Law as a Law of Rules, 56 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1175 (1989).

[2] Drawing basic faces, figures, and everyday things is totally learnable, but it seems like “art” in elementary school is either free-form nonsense, a collage, or some paint-by-number project to produce a Hallmark holiday doodad. And implicit in treating art education that way are lame assumptions about “art.” One is that practically anything is “art.” Give Congo the gorilla a paintbrush and let her swish it around on paper. Not art. That’s tool manipulation, which is evolutionarily impressive, but it’s not the neurological leap of constructing visions of the world in your mind and placing them on paper. And manipulating a gorilla for art-ideological ends is a form of animal abuse I won’t tolerate. Another assumption, which many people carry into adulthood, is that one must be “creative” to be able to draw even the simplest things. I hear people with $400K educations say things like that. Right now in a state penitentiary some guy or gal with a twisted nickname like Dragon Aneurysm, who goes by “DA,” is inking up a fellow prisoner without any stencil or projector and creating something like Taylor Swift riding a kraken over dead elves because that’s what Fentanyl Francis wanted. And while it’s possible that DA’s left index finger (right brain) was touched by the right index finger of baby Jesus conveying the special gift of the “creativity,” it’s far more likely that DA just figured it out, or if young enough, got it from the Youtube. Good basic drawing is learnable for most people (I picked it up at age 42), and it would be especially learnable for kids if someone bothered to teach them some of the basics Da Vinci gifted to us all and didn’t put up a mental wall and treat it like extra-sensory perception (which I also have). If someone wants to break down that mental barrier out there, I’ll be holding hands while the walls come tumbling down. When they do, I'll be right behind you.

[3] There is practically a mesmerizing example from brain research on every page of The Master and His Emissary, and one that gets me every time is the capacity of the left brain to make stuff up. The “bullshitter,” as McGilchrist calls it. Whether it knows something or nothing, the left brain will always have a story about what is going on that it relates with total confidence even when it is totally wrong. In this way, people with right brain damage can sometimes bear a striking resemblance to sociopaths and schizophrenics (and some lawyers). If your left-brain is totally running the show, you’re in a room where the light won’t find you, and you will not be acting on your best behavior.